by Matt Nohn, AHI Senior Advisor

Last summer I came back to India to revisit the Mahila SEWA Housing Trust (MHT; see www.sewahousing.org). I know MHT well, as I worked with them in Ahmedabad, one of India’s fastest growing cities, for three years. Still today I serve as an advisor to MHT, too. AHI and MHT are closely collaborating since around 2007, as AHI supports the larger SEWA network, to which MHT belongs, in launching a market-driven housing microfinance company that is co-governed by the urban poor.

MHT is a Mission-Entrepreneurial Entity (MEEs) founded by the Self-Employed Women Association (SEWA; see www.sewa.org). The support of poor, informally and self-employed women (and their families) to access improved housing and neighborhoods is its mission. MHT’s poor members are usually self- or informally employed—such as street vending day laborers and home-based piece-rate artisans and industrial outworkers. Particularly for the later group, rarely leaving their settlements and producing at home, housing improvements are of the highest relevance and closely related to income improvements (e.g. through access to electricity, subsequent use of more productive machines) and expenditure reductions (e.g. through better health but also reduced fees for access to subsidized or fairly priced public services).

In this regard, through slum upgrading in the scope of Ahmedabad’s Parivartan Slum Networking Program, MHT became a big player in low-income housing in India MHT implements various schemes for improving service delivery and basic infrastructure in low-income areas, especially informal ones; see e.g. https://www.box.com/s/6ui7j8zvfr8lc4lp5co8. Since inception in Ahmedabad, these poverty reduction programs have been replicated across multiple Indian states, often with the participation of MHT. For example, at present MHT works with DFID in order to replicate sanitation and solid waste service projects in Bihar, one of India’s poorest states. Since 2007 MHT, SEWA Bank and AHI collaborate in launching SEWA Grih Rin, an emerging housing finance company. To bridge the time until Grih Rin’s launch MHT works with two credit and savings cooperatives that also deliver housing finance. This work allows MHT to test new products and to innovate the housing finance space. One of these innovative products is what we call Home Asset Loan Finance at AHI: or, simply, HALF as it squares half way in-between typical microcredit and traditional mortgage finance.

No margin, no mission

Launching HALF for semi-formal properties is challenging because it requires to do all of multiple things right: failure to do so may even lead to extermination of the lender—as housing is a capital intensive product, and the lender is “nothing but” a group of poor women:

1. To screen the loanee’s probability of repayment,

as in case of any typical microfinance product

These proceedings are basically identical to any microenterprise or consumer loan.

2. To screen the security of the collateral (part 1),

proofing tenure of the land (and home), as in case of a mortgage.

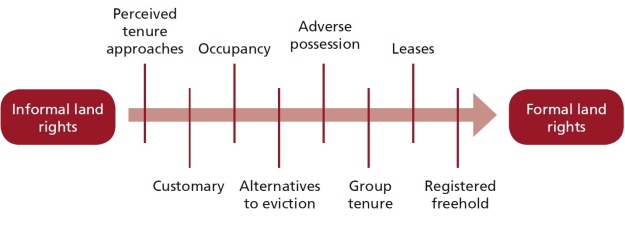

However, unlike in case of a mortgage this can be hard in case of HALF, as the underlying asset’s title is neither illegal/informal nor fully legal/formal but is placed somewhere in-between. On this regard, UN-Habitat speaks of the continuum of land rights, which also reflects in the latest Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing Raquel Rolnik to the UN Human Rights Council. Thus, how to establish the likelihood of eviction and loss of collateral?

The continuum of land rights (Source: UN-Habitat (2012). Handling Land, Innovative Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure. Accessible online at: http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=3318&alt=1)

3. To screen the security of the collateral (part 2),

eliminating potential conflict with the urban planning regime

Even if land tenure is safe, the house may still be destroyed if it was in conflict with future development—such as this road in Wenling, Zhejiang province, China.

Would you give them a loan? Will they hold out? (Source: Reuters)

Well, they did not—even though they thought the compensation wasn’t worth it. (Source: Reuters)

4. To establish contractual proceedings that, in case of default, allow the lender to take possession of the collateral—even without mortgage.

Thus, how do you make sure you get the house in case you need to take the defaulting borrower to court (in absence of mortgage foreclosure, which would allow you to just take the house even without the court.)

5. To screen the security of the collateral (part 3),

proofing the physical qualities of the collateral

Even if land tenure and construction site are safe, the lender still needs to ensure that the structural quality of the house is safe enough to e.g. withstand a disaster. Also the lender needs to ensure that the money is really invested in the construction of the tangible collateral.

Are you sure it is strong enough? (Gujarat Earthquake 2001; picture credit: CASA)

[To be continued in next week’s Part 2.]

Pingback: Mortgage emulators: pro-poor housing finance innovations (Part 2) | Affordable Housing Institute – Global Blog