By Ellie Leaning, Analyst

This is the first of a series of blog posts on the historical evolution and uniqueness of South Africa’s housing policy as seen in Cato Manor. This initial post aims to provide a historical overview of the political, economic, and cultural factors at play in Cato Manor.

Cato Manor is one of South Africa’s most historically significant townships. It sits on Durban’s periphery, tucked out of the public eye amongst the hillside, about a ten minute drive from the waterfront. I have a particular affinity to Cato Manor because I lived there for eight-weeks in 2013 with a Zulu family. This was where I had my first exposure to affordable housing projects and became acutely aware of the significance of my family’s Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) house in their quest for opportunity in a world of pervasive inequality (tune into the next post in this series for a discussion of RDP houses!).

Gardens Drive in Cato Manor with RDP houses as far as the eye can see and a mini-bus taxi parked along the street, waiting for customers. These taxis are constantly running back and forth, honking and blasting music, trying to attract a new client. While perhaps intimidating for a foreigner, these taxis are very inexpensive and very efficient (although perhaps not very safe), connecting the township to the greater Durban area.

Fun fact: As the buses do not have signs indicating their destination, the drivers (or a driver’s assistant who sometimes rides along) and passengers use hand signals to indicate where the bus is going. For instance, lifting your index finger in a circular motion will get you a ride to South Beach. This stems from Apartheid-era innovation when the government did not supply any public services to these areas – yet another example of a creative response to a market failure!

Cato Manor’s role in the monumental political, economic, and cultural changes of 20th century South Africa make it a useful and relevant case study. It was one of the main areas where the African National Congress (ANC) focused re-development efforts post-1994, and today it is frequently considered Durban’s equivalent to District Six in Cape Town. While this is a specific township with its own history, the lessons learned and the complexity of that history are representative of the rest of South Africa.

Cato Manor has a unique history that is deeply rooted and very important in its culture today. The Nqondo clan occupied the area as early as 1650, until the Ntuli clan took over about a century later. It is unclear what happened to these tribes, but in 1815 the British established Port Natal (the Portuguese word for Christmas, as Natal was first found by a Portuguese explorer on Christmas Day 1497). The Brits lived primarily on the coast, while the Zulu King Shaka controlled the interior. In 1845, George Cato became the first mayor of Durban and was given the land of Cato Manor, which he subdivided and sold to Indian market gardeners (Durban is also home to the world’s largest Indian population outside of India) who decided to remain in South Africa after their terms as indentured slaves ended. Africans began to set up shacks and informal settlements along the periphery of the area, and as more and more Africans settled in, a unique mixture of vibrant Indian and African culture appeared. These Africans were primarily Zulus, who previously ruled large parts of present-day KwaZulu Natal (KZN) and had an incredibly strong empire. The long-lasting periods of conflicts and consequent colonization were brutal and oppressive, but resulted in a strong sense of identity and pride in the Zulu Kingdom, one that is still evident today in Cato Manor and elsewhere in KZN.

In 1932, Cato Manor was officially brought into the Durban municipality, and the (mostly native African) shack-dwellers were declared illegal occupants. Regardless, Africans continued to rent homes and land from Indians (under the law at this time, Africans were not allowed to own land or build homes in urban areas), with established tenure and amicable relationships for a time. Around 1945, historians estimate that Cato Manor was home to over 50,000 Africans, who began accusing Indians of rent-hikes and overcrowding. This occurred simultaneously with the rise of the Afrikaaner National Party in 1948, which imposed a legalized racial segregation system, infamously known as Apartheid. Racial tensions exacerbated existing divides, leading to a brutal “anti-Indian war” on 13 January 1949 that left 137 dead and thousands injured.

After this, Indians began to leave Cato Manor, returning only to collect rent from Africans, who were busy building more shacks and sub-letting to more Africans. Indian landowners then sold a large portion of their land to the Durban City Council, which then developed the land as a largely unregulated and overcrowded emergency center for homeless people. This became one of the main points of unregulated production of shimeyane, a homemade distilled liqueur, and consequent chaos.

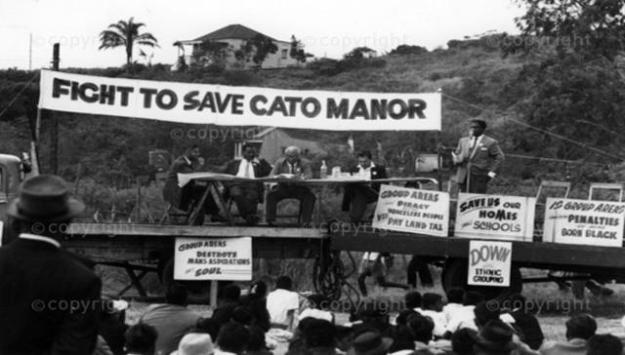

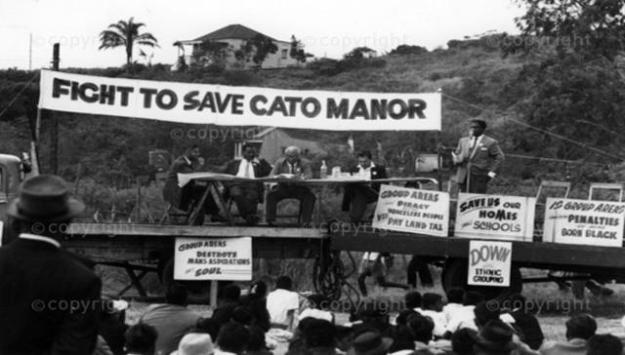

Cato Manor forced removals and police brutality in mid-1950s.

In 1950, National Party passed the Group Areas Act, the Population Registration Act, the Immorality Act, and the Suppression of Communism Act – the infamous laws of Apartheid. The 1950s marked significant increases in brutal legalized segregation and horrific race-based violence. Apartheid’s opposition, the ANC, was gaining immense power when it was forced to go underground by laws prohibiting political groups and defining anti-apartheid sentiments as equal to treason. The ANC had various underground hubs in the different provinces, and Durban’s branch was based in Cato Manor. The ANC women’s league was also largely prominent in Cato Manor around this time.

Cato Manor: October 1959.

The apartheid regime responded to this by attempting forced removals (within the law, under the Group Areas Act) to place residents in racially exclusive Indian and Black townships, such as KwaMashu and Chatsworth. These efforts were met with massive resistance and violent conflicts, but eventually the bulldozers and police forces won.

Cato Manor was mostly vacant from the late 1960s, aside from a few Hindu temples and avocado trees, a sad ghost of its vibrant history. As the anti-apartheid movements gained strength in the later 1970s, people began trying to move back, but violence plagued the region again in the 1980s. Soon after, people began proactively reclaiming their land and returning to Cato Manor. The first area which people resettled was along the ridge of Cato Manor, an area called Cato Crest. In 1994, the ANC won the national elections in a remarkably peaceful power transfer. The Zulu Kingdom was incorporated in the Province of Natal in a deal which recognized the power and presence of the Zulus in Natal while stably bringing them into the Republic of South Africa. Natal was renamed as KwaZulu Natal, in which “Kwa” denotes ownership-of or possession: the Zulu’s Natal.

The ANC, left with a broken country, attempted to implement broad changes, including a brand new constitution containing Section 26: the Right to Housing, where “Everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing”. A unique aspect of the South African constitution is that is does not only apply to South African nationals; anyone living in the country is entitled to the same rights as a citizen. In this unique aspect of the constitution, the state took on the responsibility of providing access to adequate housing for both its citizens and permanent residents. In a country of legally enforced geographic segregation of races and consequent socio-economic divides, this was no easy task. Accordingly, since 1994, South Africa has devoted a lot of time and resources to pro-poor housing initiatives, most of which were implemented in Cato Manor with varying levels of success.

Residents of Cato Manor and the larger eThekweni (Durban) municipality established the Cato Manor Development Association to upgrade and redevelop the area. Soon following this, Cato Manor was identified as a Presidential Lead Project of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which awarded R130 million ($11.2 million) for specific upgrading schemes to be explained in the next South Africa post.

The RDP house that I lived in for eight weeks with my homestay family (my little sister is at the front door)!

Today, Cato Manor is a very large and partially well developed area, yet is still plagued with violent crime, unemployment, and poor health. Cato Crest, one of the six informal settlements on the outskirts (the ‘crest’) of Cato Manor, is a place of extreme poverty and violence. Parts of Cato Manor are formally owned by their dwellers, with homes attached to the grid with relatively steady electricity and functional plumbing, while others, as in Cato Crest, are completely informal with no legal land ownership, no financial mechanisms for home improvement, no connection to grids, no sanitation, etc. The different mechanisms of housing are at play in Cato Manor, from the 1994 RDP houses, to “green streets” of solar power and efficiency upgrades, to basic slum upgrading schemes attempting to solve the dilemmas of the informal settlements.

South Africa’s, and Cato Manor’s, unique history has led to a regeneration process that is both very difficult and vitally important to get right as the country struggles for socio-economic equality. As we stress here at AHI, there is not one sector of life that housing does not touch. Housing is the keystone species of development, and Cato Manor has been a guinea pig for a lot of these initiatives.

The next blog post in this series will discuss the different regeneration and redevelopment programs at the national level and the local level – stay tuned!