This piece was originally published by Jadaliyya, an ezine produced by the Arab Studies Institute. Jadaliyya combines local knowledge, scholarship, and advocacy to better understand the Arab World and to fulfill its dedication to discussing the Arab world on its own terms. The original article can be found here.

By Maysa Sabah Shocair, AHI’s Managing Director of the GCC Region

While working as a Project Manager at the Fenway Community Development Corporation (CDC) in Boston and as a Consultant to Phipps Houses in New York City, I experienced firsthand how nonprofit developers can contribute to preserving housing affordability in central locations. Fenway CDC builds and preserves housing and champions local projects that engage the entire Fenway community in protecting the neighborhood’s economic and racial diversity. It has operated since 1973 and has developed nearly six hundred homes, housing approximately 1,500 low and moderate-income [1] residents, including those with special needs. In addition, Fenway CDC has supported residents through offering job placement and career advancement services, building playgrounds, running after-school programs for teens and operating a center for seniors. Similarly, Phipps Houses develops, owns and manages housing in New York City. Since its founding in 1905, it has developed more than six thousand apartments for low- and moderate-income families, valued at over one billion US dollars. Phipps Houses manages a housing portfolio of nearly ten thousand apartments throughout New York City. In addition, it serves over eleven thousand children, teens, and adults annually through educational, work readiness, and family support programs.

Now that I am working in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as an affordable housing consultant for several public and private entities, I often wonder: Could private nonprofit housing developers, like the Fenway CDC and Phipps Houses, make an impactful contribution to bridging the supply and demand gap in affordable housing in the GCC for both citizens and non-citizens? Could the experience of other countries with nonprofit housing developers be distilled and adapted to the GCC states?

To answer these questions, I will first discuss the main attributes of nonprofit housing developers, followed by a discussion on the shortage of affordable housing for citizens and non-citizens in the GCC and the resulting need for nonprofit housing developers. I will then recommend strategies to enable the growth of nonprofit housing developers and end with a few concluding remarks.

Domed roofs in Haram City

Nonprofits Housing Developers as Mission Entrepreneurial Entities

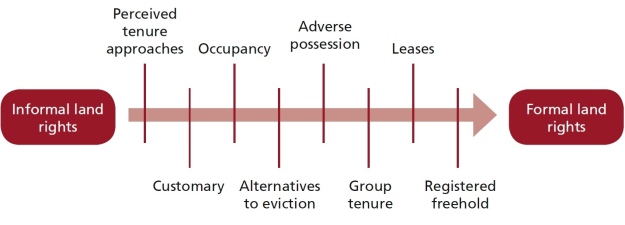

In its 2010 landmark study Mission Entrepreneurial Entities: Essential Actors in Affordable Housing Delivery, the Affordable Housing Institute (AHI) defined Mission Entrepreneurial Entities (MEEs) as “private nongovernment entities that are in the business of making housing ecosystemic change by doing actual transactions valuable in themselves that also serve as pilots and proof of concept.” MEEs could be Non-Governmental Organizations, Community Development Corporations, or Housing Associations, labels that have sometimes been used interchangeably. The study profiles twenty-three MEEs in the United Kingdom and the United States, where, in both countries, there has been a steady migration from entirely publicly managed and operated systems to hybrid public-private models, with MEEs as key delivery mechanisms.

According to the study, the three main attributes of MEEs are: (i) being mission oriented, since their goal is impact, not just profits; (ii) entrepreneurship, taking risks and persuading established institutions, including governments, to approve proposals, provide capital, etc.; and (iii) self-containment, because sustainable MEEs must make profits and maintain a positive cash flow. However, generated profits are used to further the purposes of the organizations instead of being distributed to managers and shareholders.

MEEs also share the following strengths:

· Willingness to serve populations that the private for-profit sector cannot or will not serve, including the hardest-to-house residents;

· Commitment to providing affordable housing to lower income people for the long term;

· Building strong connections with residents and the communities they serve;

· Commitment to providing various social services that lower income or special needs residents may require;

· Potential for accessing affordable land, buildings and funding through governments and philanthropic entities or individuals;

· Commitment to seeing projects through both during their early and post-delivery phases.

Given the potential of MEEs to serve populations that are not served by private or public housing provision, this essay discusses the potential relevance of this model to the GCC countries. This interrogation is critical at a time during when many GCC countries are facing a shortage of housing for low and moderate income households. It is also a time in which we are witnessing the emergence of institutionalized charitable giving that could be in part harnessed to help with housing provision. These conditions are creating a ripe environment for the growth of nonprofit housing developers, with the much needed support of the public and private sectors.